For a little fun on Hallowe’en 2021, this post provides highlights from a short, 8-page pamphlet written in the voice of a ghostly Menno Simons. The Dutch-language pamphlet is anonymous and undated, but it from the early 1780s. This was the era of the Patriot Movement against Orange family rule in the Dutch Republic. One of the leading national organizers of the Movement was the Mennonite preacher in Leiden, François Adriaan van der Kemp. The anonymous author of the pamphlet uses the voice of Ghost Menno to wag a finger at Van der Kemp and his ilk. In 2020s terms, the author seems to be “trolling” democratically oriented, anti-Orange, Dutch Mennonites of the 1780s.

You can read more about Van der Kemp at this website (https://dutchdissenters.net/wp/2015/03/quotation-kemp-1782/, and https://dutchdissenters.net/wp/2019/03/francois-adriaan-van-der-kemp/).

Post updated: 2 Nov. 2021 (see text that follows the image of the title page below)

The banner image is from a cartoon satirizing Van der Kemp from about 1786. More details about the image are available at https://dutchdissenters.net/wp/blog-themes/, as well as http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.501853 and http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.501852.

Partial transcription, and discussion of the contents

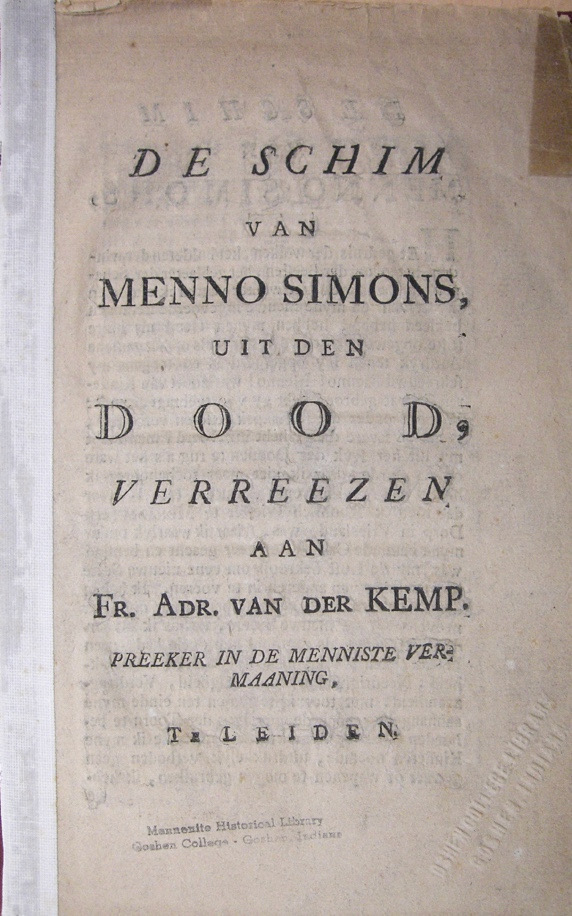

PAMPHLET TITLE: De Schim van Menno Simons, uit den dood, verreezen aan Fr. Adr. Van der Kemp, preeker in de Menniste Vermaaning, Te Leiden. 8 pp. No author, publisher, date, or place listed. (Source of the copy cited: World Cat / OCLC #13443077).

The title translates as “The Ghost of Menno Simons, Risen from the Dead, Addressing Fr. Adr. van der Kemp, preacher in the Mennonite congregation at Leiden.”

From p. 2: …men roept my uit het Ryk der Dooden te rug als het ware op de Aarde, daar ik niet meer toebehoore; ik hebbe eene verheevener Plaatse. Het is waar dat toen ik Roomsch Priester te Menaam (een Dorp in Vriesland) was, (daar ik waarlyk onder myne beminde Catholyken zeer geacht en bemind was) my de Lust bekroop om eene nieuwe Secte in navolging van anderen in te voeren.

The pamphlet is written in the voice of the ghost (schim) of Menno. Ghost Menno acknowledges that he was once a Romanist and became a deserter who formed his own sect, but he asserts that the teaching of his new sect were humility and non-resistance; his followers (children) wore simple cloths, refused to bear arms or swear oaths, and behaved as obedient subjects of government.

From p. 4: …Gy van der Kemp, gy draagt u Oproerig in de Vermaning, gy spreekt Taal die op geen Preekstoel past en vooral niet op een Preekstoel die in een Mennoniete vermaning geplaatst is, maar ik hebbe al meede vernomen dat de Mennisten te Hoogmoedig en te Laatdunkend zyn geworden om hunne Vergadering eene Vermaning te noemen, het moet Kerk zyn, hunne Leeden moeten niet naar mynen Name Mennonieten, maar Doopsgezinde genaamt worden.

Ghost Menno contrasts these teachings with the recent preaching of Van der Kemp. Ghost Menno says that such monstrous children as this (zulke ontaarde kinderen, p. 4) are not humble Mennonites but arrogant Doopsgezinden (the Dutch word for Baptizers) who presume to challenge the authority of government. Ghost Menno sarcastically questions Van der Kemp’s learning, and charges him with Socininanism and with accepting money to betray his duties as a preacher. He then charges that he is a Jesuit for refusing to pray with his whole heart for the well-being of the authorities. Ghost Menno argues that teachers in Van der Kemp’s tradition should not meddle in the affairs of state but rather use only “the weapons of faith” (de Wapenen van het geloof) (p. 7).

From p. 7: Laat Menno u nog eens en of het laatste ware, raaden. – Bid ievrig standvastig en oprecht voor de Regeering waar onder gy leeft, het zy voor die, die in Staatsbestuur, en in het algemeen voor alle die over u in het Land in Hoogheid gesteld zyn.

Menno remarks that the fashions of the 1780s (comedies, operas, concerts) are far removed from his experience. He decries these worldly attractions and calls on Van der Kemp to lead a Christian and evangelical life as an example to his congregants and all of God’s loyal servants.

The Ghost of Menno Simons (anon. Dutch pamphlet from the 1780s) (Source: Mennonite Historical Library, Goshen, IN)

Further considerations

THE TEXT BELOW IS UNDER CONSTRUCTION:

If you would like to read the entire document in the original Dutch, you can find it via Google Books. While I have consulted the copies at Goshen College and Bethel College in the US, the Google Books version is from the Dutch National Library (KB) in The Hague. I cannot see any significant differences in the copies.

It’s worth saying a little more about these various copies, however, because the bibliographic records about them include speculations on the authorship and dating of the document.

About possible authors:

It is clear enough from clues in the text that the author was almost certainly not a Mennonite. Why? Among the reasons for this conclusion is that the Ghostly Menno of the text claims to have founded “a new sect” (eene nieuwe Secte); furthermore, on the title page the author calls Van der Kemp the preacher of the Menniste congregation. These two terms are very unlikely to have been the language a Mennonite author would have used, since Mennonite supporters of the Orange regime were mostly conservative Mennonites who would have refused to conceive of their tradition as “sectarian” (a polemical category of the time), or called themselves Mennisten (a Dutch term for Mennonites that Mennonites rarely used). It’s far more likely that the author was a non-Mennonite supporter of the Orange family who was familiar with Mennonite history and was using Menno’s ghostly voice to attack Van der Kemp, quite possibly with the goal of convincing actual Mennonites who had centrist or conservative tendencies to withdraw support from Van der Kemp and the Patriot Movement. In the 1780s Van der Kemp was making a national profile for himself in the Dutch Patriot Movement as a leading critic of and activist against the Orange regime (for some details, see the links I include above), so he would have been a clear target for Orangist sympathizers and propagandists.

Who might have penned this propaganda against F.A. van der Kemp? There seem to be two possible candidates.

The bibliographical details in Google Books and in the catalogue of the KB (https://opc-kb.oclc.org/DB=1/XMLPRS=Y/PPN?PPN=398697744) both mention Philippus Verbrugge as a possible collaborator (Medewerker) in the creation of the document. The source for this possible link looks to be a book by Pieter van Wissing, In louche gezelschap: Leven en werk van de broodschrijver Philippus Verbrugge, 1750-1806 (Hilversum: Verloren, 2018), p. 236. I do not have access to this book at the moment (2 Nov. 2021). Might it be possible that Verbrugge was actually the anonymous author? At the moment, I can’t find a good biography of him to share in English, nor good reasons to agree with this conclusion. I might prepare a better English online summary for a later post, since Verbrugge does look to be a curious and important person in the Dutch political press of the 1780s.

About possible dates of publication:

The Google Books entry for the pamphlet lists the date of publication as 1780. This is certainly a mistake. “Ca. 1780,” the date listed in the bibliography of Springer and Klassen, The Mennonite Bibliography, 1631-1961, #5150, is a more accurate way of listing the date.

The bibliographical entry on the webpage of the KB (Dutch National Library) lists the date as “[1782]”. I suspect this dating is more plausible than 1780. After all, it was a year when Van der Kemp was already a national figure, partly because of his secret promotion of the revolutionary pamphlet To the People of the Netherlands (1781) but mainly and publicly because of his revolutionary preaching in 1781-82 (https://dutchdissenters.net/wp/2015/03/quotation-kemp-1782/).

The Knuttel bibliography is probably the source for the KB’s dating of [1782]. The Knuttel entry for the pamphlet (20279) lists no date in the entry, but the entry is grouped together with other texts from 1782.

A curiosity related to the dating of the text is that, judging from a quick terms search of the Knuttel bibliography, part 5 (1776-1795), Dutch authors seem to have used schim in titles only two other times in this 20-year period (Knuttel 20236 and 20276). Both of the texts in question are also listed as dating from 1782. If the search of this collection is expanded to schimmen (ghosts), then there are three further sources (two from 1780 [Knuttel 19388 and 19289) (one from 1781 [Knuttel 19590]) — all about the 17th-century Dutch naval hero Michiel de Ruyter. If the search of terms is expanded further to include geest (spirit) used in a presumably similar sense, then more titles might be worth discussion (Knuttel 19604, 19628, 19683, 19684, 19690, and 19837 — all apparently from 1781). Because I haven’t had a chance to check these other texts, I’m not confident in their use of “spirit”. For now, a preliminary hypothesis seems to be that Dutch publicists found it fashionable in the early 1780s to discuss ghosts and spirits in historical and political debates.

Because of the textual and contextual evidence, I would agree with the Knuttel and KB date of 1782 (or perhaps some time later but certainly before 1787) as the likely date of De Schim van Menno Simons. Nonetheless, without further evidence, the date will have to remain a speculation. My suggestion: “Ca. 1782” is the best description, for now.

More speculation:

Regardless of the author’s identity or the date of the text, De Schim van Menno Simons looks to be an example of trolling in 18th-century social-media (i.e., pamphleteering) terms.

For a short biography of F.A. van der Kemp, plus a bibliography of works by and about him, see: