Cover of a 2008 catalog that accompanied an exhibit in 2008-9 at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam. The translation of the catalog title is “Romeyn de Hooghe: the late Golden Age brought to life.”

Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708) is a major figure in the world of European art history in the era of the Dutch Golden Age. What’s more, he played a significant role in Anglo-Dutch politics around the time of the Glorious Revolution as a supporter of William of Orange / William III. He’s been the subject of a significant number of exhibitions and academic studies recently. For example, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, has just finished an exhibit on “The Book Illustrations of Romeyn de Hooghe” (13 Sept. 2014 to 25 Jan. 2015). In this post I introduce an anonymous etching that I think might be by him (or maybe by his student Adriaan Schoonebeek).

Note: Since first publishing this post I have updated it a few times. One revision was from Feb. 8, and more thorough revisions are from Feb. 11 and 23. The main change in the most recent, thorough revisions is to downplay the importance of the 1660 edition of Hortensius.

BACKGROUND: My interest in Romeyn de Hooghe was sparked by the Faultline 1700 conference in Utrecht in January. In particular, Henk van Nierop, Trudelien van ‘t Hof, and Frank Daudeij gave papers that focused on his significance. As a scholar of Mennonites, I was intrigued by the connections de Hooghe had with the Bidloo brothers (Govert and Lambert). After the conference, I was curious to learn more about de Hooghe’s Mennonite connections, and in the week that followed I visited a few libraries and talked with a couple of friends with expert knowledge on Mennonites in the arts (Rineke van Nieuwstraten and Piet Visser). During this tour I took numerous photos of documents and made a few notes. When I returned to Canada in early February and reviewed my data and my memory of conversations, I was struck by Piet Visser’s suggestion that de Hooghe may have created the frontispiece for an anti-Anabaptist history. Since first posting this blog entry about the etching, I’ve received feedback from several people and checked with Wouter Meeder at the library of the Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente te Haarlem (VDGH), where I thought I had photographed a version of the etching in a book from 1660. I couldn’t have, it turns out. The VDGH does not have such a book in its collection. I seem to have had a minor Brian Williams moment while preparing the first version of this post.

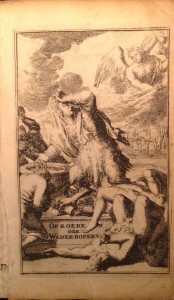

UPDATED DETAILS: The etching in question is an unsigned frontispiece. Originally (but probably incorrectly [see below under “open question 1”]) I thought it first appeared in the 1660 Dutch edition of Lambertus Hortensius’s anti-Anabaptist history: Tumultuum Anabaptistarum liber unus (1548). You can find a high-quality, zoomable scan of the frontispiece at the website of the University of Amsterdam:

I cannot now confirm my earlier claim that the etching first appeared in 1660. The image above is from the 1699 edition of Hortensius. By checking the images attached to entries in the Short Title Catalogue of the Netherlands I have confirmed that the frontispiece is included in the editions I have marked in the bibliography below (thanks to Jo Spaans and Wouter Meeder for their tips). These editions date from 1694, 1695, 1699, and 1700. The image is not included in Piet Verkruijsse’s short title list of de Hooghe’s work, which is found at the end of Henk van Nierop (ed.), Romeyn de Hooghe: De Verbeelding van de late Gouden Eeuw (2008) — with a preparatory version online (see the “Subjectieve bibliografie in STCN-format” for a list in the format found in the book).

TWO OPEN QUESTIONS:

1. What is the earliest version of the frontispiece? The earliest version that I can confirm is from 1694. I still wonder, however, if there might be editions of Hortensius from before 1694 with the image. The anonymous frontispiece artist was certainly influenced by earlier images from Hortensius’s Oproer. For example, there is the image below from the 1614 Dutch edition of Hortensius, which probably inspired part of the background in the anonymous frontispiece from 1694-1700:

Anabaptists on the execution field, from Hortensius (1614 Dutch edition). Source = Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The earlier etching is also by an anonymous artist, and it is based on a painting by Barend Dircksz that used to be in the Amsterdam city hall but is now lost. Since I’m not near a good Dutch research library, I cannot check these questions.

2. Who created the frontispiece? This question is related to the first question, because if there are confirmed versions of the etching from any earlier than 1660, then Romeyn de Hooghe cannot be the artist (he was born in 1645). Below are two thoughts:

a. I agree with Piet Visser that the frontispiece looks to fit the enigmatic, symbolically rich style of de Hooghe’s known etchings. However, I’m not an expert, so I let other readers judge for themselves. Below you can compare two details from the anonymous etching and from a piece signed by de Hooghe.

Detail from Romeyn de Hooghe’s frontispiece to Johannes Antonides van der Goes, De Ystroom, 1685 (Source = National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; online exhibit catalog)

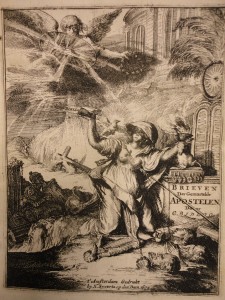

Trudelien van ‘t Hof has also pointed out some general parallels between the overall composition of the anonymous frontispiece and this frontispiece below from a signed de Hooghe frontispiece from Govert Bidloo’s Brieven der gemartelde apostelen (1675):

The comparisons are not overwhelming reasons for attribution, and I should emphasize again that I am not an expert on de Hooghe’s work. However, I think the similarities suggest that there is a possibility that de Hooghe created the anonymous work.

b. The publisher of the 1694 and 1699 editions of Hortensius (with the frontispiece) was Adriaan Schoonebeek, one of de Hooghe’s students (and incidentally also the art dealer for Peter the Great of Russia for a while). I know very little about Schoonebeek. One possibility is that he was the artist of the anonymous etching. This is currently my best bet.

I would be grateful for any feedback from experts on Romeyn de Hooghe’s career and art. Add a comment below or send me an email.

BIBLIOGRAPHY of some editions of Hortensius (there are earlier editions)

* the sources is the STCN.nl and the University of Ghent

* title in bold text have the anonymous frontispiece (the others [especially the later one] may also include it, but I have not been able to confirm this)

- 1659, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Van den Oproer der Weder-Dooperen. Translated by Cornelis Gijsbertsz Plemp. Published by Jan Jacobsz Schipper.

- 1660, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Oproeren der Wederdoperen; geschiet tot Amsterdam, Munster en in Groeningerlandt. Published by Samuel Imbrechts.

- 1667, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Oproeren der Wederdoperen; geschiet tot Amsterdam, Munster en in Groeningerlandt. Published by Samuel Imbrechts.

- 1694, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Verhaal van de Oproeren der Wederdoopers, voorgevallen te Amsterdam, Munster en in Groeninger-Land. Published by Adriaan Schoonebeek.

- 1695, Paris: Lambertus Hortensius, Histoire des Anabatistes [sic] ou Relation Curieuse de leur Doctrine, Règne & Revolution. Translated by François Catrou. Published by Charles Clouzier.

- 1699, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Verhaal van de Oproeren der Wederdoopers, voorgevallen te Amsterdam, Munster en in Groeninger-Land. Published by Pieter Wittebol and Adriaan Schoonebeek.

- 1700, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Histoire des Anabaptistes: Contenant leur Doctrine, les Diverses Opinions qui les Divisent en Plusieurs Sectes. Translated by François Catrou. Published by Jaques Desbordes.

- 1702, Amsterdam: Lambertus Hortensius, Histoire des Anabaptistes: Contenant leur Doctrine, les Diverses Opinions qui les Divisent en Plusieurs Sectes. Translated by François Catrou. Published by Jaques Desbordes.

- 1733, Paris: François Catrou, Histoire du Fanatisme dans la Religion Protestante, Depuis Son Origine. Includes Catrou’s earlier translation of Hortensius.